| |

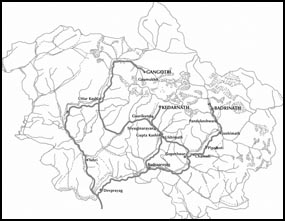

At the tender age of eleven Nilkanth Varni

travelled alone in the northern region of India (Uttarakhand). He

started his upward pilgrimage to Kedarnath from Rishikesh and then

went to Badrinath. From Badrinath he embarked upon an extremely arduous

and difficult journey to Badrivan in the beginning of winter. Nilkanth

stayed there for three months and then travelled through the most

dangerous and frigid terrains of the world to Kailas and Manasarovar.

From Manasarovar Nilkanth Varni returned to Badrinath after six months.

From here he started another challenging pilgrimage to Gangotri (10,000

ft.).

In this article we shall look at the conditions and hardships Nilkanth

must have faced through the experiences of other explorers.

Nilkanth's

trek route in the Himalayan pilgrim places (Uttarakhand) was different

from today's roads and trekking pathways. The route of his journey

by foot was extremely difficult and unimaginable. Nilkanth's

trek route in the Himalayan pilgrim places (Uttarakhand) was different

from today's roads and trekking pathways. The route of his journey

by foot was extremely difficult and unimaginable.

When Nilkanth left Rishikesh on 16 September 1792 towards Kedarnath,

he travelled through the towns and villages of Devprayag, Rudraprayag,

Gupta Kashi, Triyuginarayan and Gaurikund. The Shri Haricharitramrut

Sagar describes Nilkanth's journey with all the names and the number

of days he stayed at the pilgrim places he passed on his way to Kedarnath

(as mentioned above). Today's route from Rishikesh to Kedarnath is

the same as it was in Nilkanth Varni's time. But Nilkanth had two

options for his journey from Kedarnath to Badrinath. (See above map.)

Route

1: Kedarnath, Gaurikund, Triyuginarayan, Gupta Kashi, Rudraprayag

Chamoli, Joshimath, Vishnuprayag and Badrinath. Route

1: Kedarnath, Gaurikund, Triyuginarayan, Gupta Kashi, Rudraprayag

Chamoli, Joshimath, Vishnuprayag and Badrinath.

Route 2: This narrow path by foot was used less by pilgrims: Kedarnath,

Gaurikund, Gupta Kashi, Ukhimath, Chopta, Gopeshwar, Chamoli, Joshimath

and Badrinath.106

Nilkanth, instead of choosing from one of the above two routes, blazed

a new trail altogether. Shri Haricharitramrut Sagar notes, "In

the Himalayas at Kedarnath there is a big mandir of Mahadev. Brahmachari

(Nilkanth) took the direction behind Kedarnath towards Badrinath.

He reached Badrinath after nine days."107

So, Nilkanth, instead of taking the two familiar and popular routes

one and two (as mentioned above, where one passes through the pilgrim

places of Ukhimath, Gopeshwar, Joshimath, etc., went around the mountain

behind Kedarnath towards Badrinath.

Now let us look at the geography of this region.

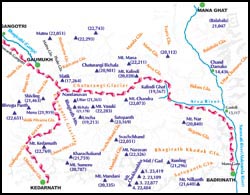

The description in Shri Haricharitramrut Sagar is very clear. It says

that to the north of Kedarnath lies Mt. Kedarnath. It seems that Nilkanth

had trekked around Mt. Kedarnath towards Badrinath. But is there such

a path or way? And to circle around Mt. Kedarnath Nilkanth would have

to cross the Chhodabari and Dudhganga glaciers. Further ahead he would

have to pass through the Kirti glacier and a clear yellow glacier

that lies in a valley between Mt. Kedarnath (22,769 ft.) and Mt. Meru

(21,919 ft.). After traversing these glaciers one reaches the Gangotri

glacier. After crossing it one has to walk in the valley of the Bhagirath

mountain range to reach Nandanvan. Then by crossing the Chaturangi

glacier and the subsequent Kalindi Ghat (19,567 ft.) one arrives in

the valley where the river Arva flows on the Arva glacier. On walking

along the banks of river Arva the latter merges into the river Alaknanda

near Gastoli. Then on walking 11.5 km south from here one arrives

at Badrinath.

It seems that Nilkanth travelled on this route. Despite the simple

description of the route, in reality, it is nothing but full of harsh

terrains and insurmountable difficulties. Any adventurous and enterprising

traveller or pilgrim would never be able to source enough courage

to do it alone. Such are the perils and impossibilities of this land.

It took Nilkanth nine days to travel a distance of 125 km over seven

glaciers. This means that Nilkanth could barely cover nine to twelve

kilometres everyday.

When Nilkanth first arrived at Badrinath he stayed there for twenty

days. Then he stayed at Joshimath for a few days before embarking

upon his pilgrimage to Manasarovar on 17 October 1792. After six months

he returned to Badrinath (as described in previous articles). But

his return to Badrinath was not the end of his pilgrimage.

When Nilkanth returned to Badrinath it was 13 May 1793, Akha Trij.

From here Nilkanth decided to go to Gangotri. And the only one known

path was to descend to Joshimath again and go to Chamoli, Gupta Kashi,

Triyuginarayan, Buddha Kedar and finally Gangotri. But the Shri Haricharitramrut

Sagar describes and points to something different altogether.

When Nilkanth returned to Badrinath after his pilgrimage to Manasarovar

he met Maharaja Ranjitsinh of Punjab. The king was captivated by the

divine personality of Nilkanth. Out of adulation for Nilkanth he requested

him to come to his kingdom. But Nilkanth refused. When the king and

his party were about to leave for Joshimath and travel to Haridwar

he asked Nilkanth again to come with him. But Nilkanth wanted to go

to Gangotri. If Nilkanth had wanted to take the known path to Gangotri

then he would have descended with Maharaja Ranjitsinh to Joshimath.

But Nilkanth, instead, decided to take a different route to Gangotri.108

Now the question is which different route did Nilkanth take?

Nilkanth took the same route he had taken while coming from Kedarnath

to Badrinath. The path was geographically familiar to him because

he had travelled on it during his journey from Kedarnath to Badrinath.

Then on reaching the Gangotri glacier he travelled towards the source

of river Ganga at Gaumukh and then to Gangotri. (See map on p. 30.)

The path from Badrinath to Gangotri is extremely challenging and deadly.

On the way, it is very hazardous to cross the Kalindi Ghat at 19,567

ft.109 About 125 years after Nilkanth's journey, when a European traveller

called Bernie had travelled on the same route from Badrinath to Gangotri

with guides and necessary paraphernalia the local people of the Garhwal

region were amazed. In comparison it is intensely fascinating as to

how Nilkanth, who at the age of only twelve, wearing a loincloth,

barefooted and with no materials or means whatsoever, pilgrimaged

alone to Gangotri. His is an unparalleled story of courage, confidence,

determination and divinity.

To understand the depth of Nilkanth's pilgrimage it would suffice

to read the experiences of Swami Prabodhanand.110 We have quoted the

experiences of Swami Prabodhanand in the previous articles of this

issue (p. 14). The description of his experiences of the entire pilgrimage

is awe-inspiring.

A Unique

Pilgrim to The Source of Ganga

For millennia mother Ganga has been nourishing India with her pristine,

divine waters. The holy river is central to the faith of all Hindus.

It is worshipped by thousands with arti everyday; its waters are sprinkled

to drive away evil spirits and all that is inauspicious and impure;

and millions of Hindus vest their faith in its redemptory powers.

It is difficult to evaluate the glory that mother Ganga has for all

Hindus.

Out of a challenging curiosity and glory for Ganga were born many

explorers and pilgrims. They endeavoured to the source of the boisterous

river Ganga. But their odysseys through the soaring Himalayan peaks

and valleys were stories of human courage and tragedy. Despite the

adversities and challenges, the mission of discovering the source

of river Ganga four centuries ago was so important that the then Mughal

ruler, King Akbar, at the end of the 16th century, commissioned a

team.111 Then with the advent of the British, who came under the pretext

of trade and then ruled India, many Europeans trekked in the Himalayan

mountains to find the river's origin. In the 17th and 18th centuries

many explorers lost their lives. Then history remains mute till the

19th century as to how many and who had reached the source of river

Ganga. The renowned 19th century writer T.N. Colebrook writes in his

1812 research paper 'On the Source of the Ganges in the Himadri or

Emodus' that the source of river Ganga was a burning issue.112 So

many explorers had died or were proved wrong in finding the source

of the mighty Ganga. Historians testify that till the beginning of

the 19th century no one was successful in finding the source of Ganga.

The reason being that the path from Gaumukh to Gangotri (21 km) was

extremely difficult and dangerous. Even today, with all the required

equipment and arrangements for the journey one experiences, to some

extent, the challenges it poses. Another reason in not finding the

source was due to Pauranic beliefs. According to tradition Hindus

believe that Ganga flows from Lord Shiv's head. The Matsya Puran says,

"Bhagirathi Ganga flows from Lake Mandod which lies in the valley

of Mt. Kailas." (Matsya Puran, Ch. 214.) The great poet Kalidas

writes in Meghdut (Purva Megh, 65) that Ganga flows from Mt. Kailas.

Hence the Hindus have come to believe that the source of river Ganga

lies on Mt. Kailas or Manasarovar. Hence, many Hindus, regardless

of the hardships, dangers and possibilities of death, pilgrimaged

to Manasarovar to find the source of Ganga. Even foreign traders and

rulers, too, travelled to find the source of Ganga. The map of Tibet,

by French traveller, D'Anville, in 1733, called, 'Carte Générale

Du THIBET', shows that "...the Ganges issues from Manasarovar."113

Two hundred years ago, sannyasi Purangir went to Gangotri in his search

for the source of Ganga. "Purangir believed that the Ganges had

its source on Kailas and flowed thence to Manasarovar."114

Sven Hedin, the Swedish explorer, writes in his book Trans-Himalaya,

"The source of the Ganges was discovered in 1808... The expedition

was accomplished by Lieutenant Webb and the captains Raper and Hearsey.

It followed the track of Antonio de Andrade. Two hundred years earlier

this trekker on his way over Mana pass to Tsaparang had, without knowing

it, passed by the source of the Ganges. The source of the Indus, Sutlej,

and Brahmaputra neither Catholic missionaries nor any one else had

passed before the year 1907.

"The instructions given to Lieutenant Webb by the supreme Government

of Bengal contain the following paragraph: 'To ascertain whether this

(i.e. the cascade or subterraneous passage at Gangotri) be the ultimate

source of the Ganges; and in case it should prove otherwise, to trace

the river, by survey, as far towards its genuine source as possible.

To learn, in particular, whether, as stated by Major Rennell, it arises

from the Lake Manasarobar; and, should evidence be obtained confirming

his account, to get, as nearly as practicable, the bearing and distance

of that lake.' "116

At this point it is necessary to mention again that history should

note that fifteen years earlier than Lieutenant Webb and his party

12-year-old Nilkanth had reached the source of river Ganga alone and

without any means and wearing only a loincloth. The path that Nilkanth

had taken on his journey from Badrinath to Gangotri is the path to

the source of river Ganga.

The river Ganga's source lies at Gaumukh (a gorge shaped like a 'cow's

mouth'), that is 21 km east of Gangotri. But the 18th century Jesuit

father Joseph Tieffenthaler "...affirms that it (the source)

will never be discovered because the way beyond the gorge of the 'cow's

mouth' (gaumukh) is impassable."117 Nilkanth had travelled from

beyond the gorge and reached Gaumukh. Then he walked from its source,

along its banks to Haridwar.

Sven Hedin writes, "The envoys (sent by King Akbar at the end

of the 16th century) saw the water of the river (Ganga) gush out in

great abundance in a ravine under a mountain which resembled a cow's

head... English explorers, however were soon to establish the fact

that the information which Akbar's envoys brought to their master

was correct."118

No British and European historians and writers have noted as to whether

any sannyasi or sadhu had reached the source of the Ganga at Gaumukh.

There is a possibility that Nilkanth's pilgrimage to the source of

Ganga, as a 12-year-old child yogi, could well be the first in the

records of history.

The seven year sojourn of Nilkanth throughout India is full of unknown

facts and revelations of the challenges he faced. When his other journeys

will be presented in future in context with the records of those who

have endeavoured we hope to get further perspectives and insights

into Nilkanth's divine personality!

Footnote

106. Poddar, Hanumanprasad. Kalyan (Tirthank).

Gorakhpur: Gita Press, 1957: 53-60.

107. Swami Shri Siddhanandmuni (also known as Swami Adharanandmuni).

Shri Haricharitramrut

Sagar. Varanasi: Swami Hariprakash, Pundit Shrinarmadeshwar Chaturvedi,

1972: 2-15-18-19.

108. Swami Adharanandmuni. Shri Haricharitramrut Sagar, Pt. 1. p.

122-124.

109. Swami, Anand. Baraf Raste Badarinath. Amdavad: Balgovind Prakashak,

1970: 67- 72.

110. Swami, Anand. Baraf Raste Badarinath. p. 67-72.

113. Hedin, Sven. Trans-Himalaya, Vol. 3. p. 209.

114. Hedin, Sven. Trans-Himalaya, Vol. 3. p. 208.

115. Hedin, Sven. Trans-Himalaya, Vol. 3. p. 211.

116. Hedin, Sven. Trans-Himalaya, Vol. 3. p. 211.

117. Hedin, Sven. Trans-Himalaya, Vol. 3. p. 199.

118. Hedin, Sven. Trans-Himalaya, Vol. 3. p. 200.

Bibliography

- Sven Hedin. Trans-Himalaya, Discoveries

and Adventures in Tibet. London: Macmillan and Co. Limited. (1913)

Vol. 3.

- S. G. Burrad and H. H. Hayden. A Sketch

of the Geography and Geology of the Himalaya Mountains and Tibet.

Delhi: Survey of India. (1934) part-3.

- Edwin T. Atkinson. Religion in the Himalayas.

New Delhi: Cosmo Publications, (1974) Reprinted.

- Swami Pranavananda. Kailas-Manasarovar,

Calcutta: S. P. League, Ltd. (1949) 1st. ed.

- Jagdish Kaur. Badrinath: A Study in

Site Character, Pilgrims Patterns and Process of Modernisation. The

Himalayan Heritage. Delhi: Gian Publishing House, (1987) 1st ed.

- James Baillie Fraser. The Himala Mountains.

Delhi: Neeraj Publishing House, 1st Reprint 1820, Reprint 1982.

- Father Giusepee. An Account of the Kingdom

of Nepal. Asiatic Researches. Calcutta: Asiatic Society, (1794), Re-printed:

New Delhi, Cosmo Publications (1979), Vol. 2.

- Jonathan Duncan, ESQ. An Account of

Two Fakeers, With their Portraits. Asiatic Researches. Calcutta: Asiatic

Society, (1808), Re-printed: New Delhi, Cosmo Publications (1979),

Vol. 5.

- Edwin T. Atkinson. The Himalayan Gazetteer.

Allahabad: The Himalayan Districts of the North Western Provinces

of India. (1882), New Delhi, Cosmo Publications (1973), Vol. 3, Part

1 and Part 2.

- Nigel Nicolson. The Himalayas, The World's

Wild Places. Amsterdam: Time-Life Books, B.V. (1985).

- Rai Pati Ram Bahadur. Garhwal, Ancient

and Modern. Gurgaon: Vintage Books. (1992).

- Rathin Mitra. Temples of Garhwal &

Other Landmarks. Dehradun: Garhwal Mandal Vikas Nigam Ltd, (1994)

1st ed.

- Ramsharan Vidyarthi. Kailas-path Par.

Delhi: Sharda Mandir Limited (1902).

- Tarun Vijay. Kailas-Manasarovar Yatra,

Shakshat Shiv se Samvad, Dehradun: Rutvik Publication (1994). First

Edition.

- Swami Shri Siddhanandmuni. Shri Haricharitramrut

Sagar (in poetry, Hindi), Pub. Swami Hariprakash, Pundit Shrinarmadeshvar

Chatruvedi, Varanasi. Shri Swaminarayan Mandir, (1972).

- Swami Shri Adharanandmuni. (or Swami

Siddhanandmuni) Shri Haricharitramrut Sagar (in Gujarati prose). Shri

Swaminarayan Mandir Sahitya Prakashan Mandir, Gandhinagar, (1995).

- Hanumanprasad Poddar, Pub. 'Kalyan'

(Tirthank), Gorakhpur: Gita Press (1957).

- Swami Anand. Baraf Raste Badarinath.

Amdavad: Balgovind Prakashak (1970).

- Maganlal J. Bhuta. Uttarapath. Mumbai:

Parivrajak Prakashan (1977).

- Maharaja Bhagvatsinhji, Bhagvadgomandal,

Rajkot: Pravin Pustak Bhandar (1986), Vol. 7..

.

Research

& Gujarati text: Sadhu Aksharvatsaldas

Translation:

Sadhu Vivekjivandas

Further related

articles will be placed on the set dates in this section |

|