|

|

At

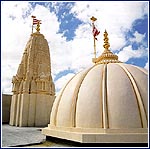

the end of a cul-de-sac in the heart of industrial Avondale in Auckland'

s western suburbs, an exotic, ornate building towers over its warehouse

neighbours in both height and style. Alice Shopland went to take a look. At

the end of a cul-de-sac in the heart of industrial Avondale in Auckland'

s western suburbs, an exotic, ornate building towers over its warehouse

neighbours in both height and style. Alice Shopland went to take a look.

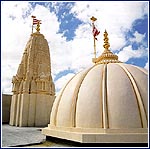

The first New Zealand temple of the Swaminarayan

sect of the Hindu religion is due for completion at the end of April.

but it's already had its official opening. The

international leader of the sect. 81-year-old Pramukh Swami Maharaj, was

here in mid-February to consecrate the $7m, 2,500m2 building, whose full

title is the Shri Swaminarayan Mandir and Cultural Complex.

More than 1500 devotees from New Zealand and overseas celebrated the opening.

The sect has a million devotees worldwide, and the Avondale temple is

the 416th Swami Maharaj has consecrated. During the opening ceremony,

marble deities were installed in the prayer room, surrounded by an elaborate

gold altar of fibreglass cast in India and assembled on-site. Blessed

by Swami Maharaj, the statues are now considered to contain the spirits

of the deities they represent. They are offered food and drink three times

a day, and their embroidered garments are changed daily.

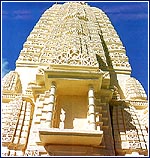

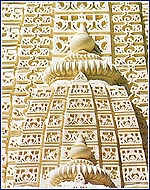

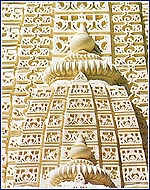

The extensive decorations adorning the concrete shell designed by Tse

Group and built by Ebert Construction are of fibreglass-reinforced concrete.

They were cast in India from sandstone originals using a rubber mould,

and shipped here in their hundreds. The temple is being painted pale pink,

in imitation of the original sandstone.

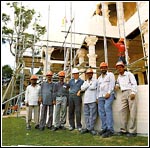

Unfortunately

many of the pieces suffered in transit, and the six craftsmen who came

from India for the task worked feverishly to mend pieces and to plaster

the ornate exterior of the seven domes. They worked from dawn to dusk

every day except on the day of the new moon. Ebert contractors also worked

long hours to ensure the temple was as complete as it could possibly be

by opening day. Unfortunately

many of the pieces suffered in transit, and the six craftsmen who came

from India for the task worked feverishly to mend pieces and to plaster

the ornate exterior of the seven domes. They worked from dawn to dusk

every day except on the day of the new moon. Ebert contractors also worked

long hours to ensure the temple was as complete as it could possibly be

by opening day.

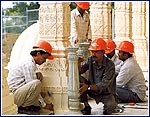

Each window frame consists of eight separate pieces of cast concrete.

The window heads alone weigh some 350kg apiece. All of the decorative

elements are attached to the building by stainless steel dowels. Les Honeyfield,

Ebert site manager for the project, estimates that fixing all the pieces

over the whole building will use more than two kilometres of stainless

steel rod - each window head, for example, requires six rods to be absolutely

certain it's not going to succumb to gravity. Similarly, each pillar comprises

about 10 elements, each of which comes in two halves to be reunited around

the reinforced core required by local building standards.

The towering main dome on the roof of the structure was bulked up by layering

1000 bricks and 500 paving slabs in with the plaster. The interior of

the dome, in the ceiling of the prayer room, is of cast fibreglass which

required 30 litres of bonding to make it good, according to Les Honeyfield.

Before

taking the decision to build, the group looked at local warehouses and

churches which were for sale, but they all needed so much alteration to

meet the sect's needs and planning requirements, that it made sense to

start afresh. Before

taking the decision to build, the group looked at local warehouses and

churches which were for sale, but they all needed so much alteration to

meet the sect's needs and planning requirements, that it made sense to

start afresh.

'Usually our temples start in an existing building, then we sell that

and build a purpose-built temple," says Navan Patel, a coordinator

for the group, which had previously met in people's homes and in hired

school halls. "We were lucky to be able to skip that step."

So now, instead of renting space from other groups, the sect is able to

rent out its own large first- floor meeting room - complete with sprung-floored

stage, control rooms and quality light and sound systems - to community

groups. so long as they meet the religious requirements such as no smoking,

alcohol or meat.

This is the first time the sect has used cast concrete to decorate a temple

- but there are temples overseas with fibreglass decorations, including

a massive 9,300m2 temple opened in Chicago two years ago. A Swaminarayan

temple in Kenya is decorated inside and out with solid teak, including

the inside of the dome. The sect's London temple is all of stone: Italian

marble inside and Bulgarian sandstone outside. Both stones were shipped

to India for carving, then shipped to London in 26,300 pieces.

The

Avondale temple doesn't quite reach these proportions, yet its impressive

commercial (and strictly vegetarian) kitchen is designed to cater for

up to 3000 people at a time - when Progressive Building visited, several

vast pots more than a metre across were being used to cook rice and lentil

soup. This is such a serious kitchen that the waste disposal has a three-phase

motor. The

Avondale temple doesn't quite reach these proportions, yet its impressive

commercial (and strictly vegetarian) kitchen is designed to cater for

up to 3000 people at a time - when Progressive Building visited, several

vast pots more than a metre across were being used to cook rice and lentil

soup. This is such a serious kitchen that the waste disposal has a three-phase

motor.

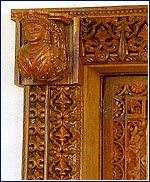

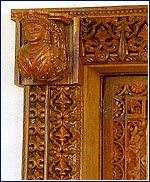

The carved solid teak doors - there are several pairs on the ground floor

and the first floor - each took three months to carve. They were installed

just before the official opening, and caused some interesting hardware

challenges because of their weight and because their precise form wasn't

known until they arrived.

'In India they work in imperial measurements," Honeyfield says, "and

there have been a few mistakes in conversion. It's kept it interesting

for everybody!"

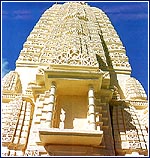

Ebert had to wait for the shikhar, the nine-metre-tall top section of

the altar which stands above the roof and is visible from quite a distance,

to arrive before plastering the prayer room ceiling.

"It weighs 55 tonnes, and it deflected the ceiling by 60mm. It would

have cracked the plaster if we'd done that first."

In many respects it sounds as though it could have been a nightmare job

for Honeyfield, but he's calm even just before opening day, and says the

clients have all been very easy and helpful to deal with.

One day at a time

By

all accounts, local input into the designing and building of an 'authentic'

Hindu temple in Auckland has helped make it a success, but not without

a few small hiccups. By

all accounts, local input into the designing and building of an 'authentic'

Hindu temple in Auckland has helped make it a success, but not without

a few small hiccups.

One was a shortage of critical design information, which kept the designer

of the structure (TSE Group) and the main contractor (Ebert Construction)

wondering what might be coming next.

The concrete block structural shell of the temple, for instance, was designed

and built without full details of many of the precast design elements

the client wanted to include in the finished temple.

"The precast components were either still being made in India, or

on the water," says Ebert  Construction

site manager Les Honeyfield. "No-one here knew quite what to expect,

so we just got on and did what we thought would work best." Construction

site manager Les Honeyfield. "No-one here knew quite what to expect,

so we just got on and did what we thought would work best."

The team was advised, for example, to expect a dome and decorative concrete

elements for the outside of the building. But exact information wasn't

available. It was a matter of wait and see, and then redesigning and reconstructing

the building where necessary.

Elements such as the all-important decorative columns were also handled

differently. "In India they are left unreinforced," says Les.

"They tell me no temple has yet fallen down, but here they need to

be reinforced - not so much to support the building but just to support

themselves. So we've put an RHS beam inside each column and tied the column

sections to it."

The columns and window surrounds presented another unforseen challenge

when they arrived on site.  These

components are cast in India, in a rubber mould taken from sandstone originals.

But to retain their shape the moulds must be well-supported during casting.

Many of the finished elements, when unpacked from their shipping containers,

were found to have twists or winds, which made it difficult to line them

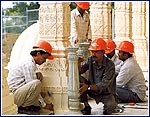

up on the building. Fortunately, the temple tradesmen who were flown in

from India to assist with the detailing, were adept at smoothing out visual

discrepancies by hand. These

components are cast in India, in a rubber mould taken from sandstone originals.

But to retain their shape the moulds must be well-supported during casting.

Many of the finished elements, when unpacked from their shipping containers,

were found to have twists or winds, which made it difficult to line them

up on the building. Fortunately, the temple tradesmen who were flown in

from India to assist with the detailing, were adept at smoothing out visual

discrepancies by hand.

While the exterior block walls of the temple were rendered by an Auckland

plasterer (Ali's Plastering) with standard cement render, up to 14 additional

tonnes of cement were used by the temple tradesmen to replaster the domes

and build up the decorative elements where they thought it was needed.

The temple tradesmen prefer a very rich and dry plaster and like to build

up an area and then scrape it away again until it is the right shape.

Most shaping is done by eye. but when making a moulded, curved balustrade

railing, a template was  used

to create a rough decorative proñle. The handrail was made on the

ground - at its core a 12mm reinforcing rod embedded in a layer of concrete.

It was first plastered and shaped by the curved plywood profile to get

an approximate look. A veiny rich cement/lime slurry was then skim coated

over the top to give it a hand-finished look. After it had cured it was

carried upstairs, cut to length and fixed to the decorative balusters. used

to create a rough decorative proñle. The handrail was made on the

ground - at its core a 12mm reinforcing rod embedded in a layer of concrete.

It was first plastered and shaped by the curved plywood profile to get

an approximate look. A veiny rich cement/lime slurry was then skim coated

over the top to give it a hand-finished look. After it had cured it was

carried upstairs, cut to length and fixed to the decorative balusters.

For Les Honeyfield, watching the temple tradesmen do things the Indian

way was half the fun of it. "I've really enjoyed this project,"

he says, "and I've got a lot of admiration for their skills. But

I've suggested a number of things to the client which could streamline

the building of future temples. I think it would work better if all the

wall elements were on site before the project starts (that way you can

see what you are dealing with) and if tilt panel construction was used

instead of concrete block construction. This would allow the decorative

wall elements - and there are  a

lot - to be cast insitu as part of the wall. a

lot - to be cast insitu as part of the wall.

"Also. I don't know what precast elements cost to produce in India,

but it may be more efficient to supply moulds to the local contractor

and let the casting be done on location. This would reduce transport costs

and transit damage, and give the contractor the opportunity to cast extra

elements if and when they are needed."

In making these practical and helpful suggestions, isn't Les Honeyfield

in danger of being offered a job as an international temple project manager?

He laughs it off. "Yeah, right, I don't know how well that idea would

go down with my wife." |

|