| |

Sushrut compiled the knowledge and teachings of his guru Divodas Dhanvantari,

King of Kashi, in the Sushrut Samhita. It was common for surgeons

then to be associated with kings, as has been cited in the Rg Veda,

Mahabharat, Sushrut Samhita and Kautilya’s Arthashastra. Sushrut

and his descendants are said to pre–date Panini, the great Sanskrit

grammarian. Patanjali in his Mahabhashya and Katyayan in the Varttika

also mention Sushrut. However scholars ascribe Sushrut’s true

period to 1000 BCE (Sharma 1999: 87).

During his era, surgery formed a major role in general medical training.

It was known as Shalya–tantra – Shalya means broken arrow

or sharp part of a weapon, and tantra means manoeuvre. Since warfare

was common then, the injuries sustained led to the development of

surgery as a refined scientific skill.

Apart from being a treatise primarily on surgery, the Sushrut Samhita

encompasses the other seven Ayurvedic faculties. Sushrut also details

surgical procedures in other specialised branches which warrant surgery,

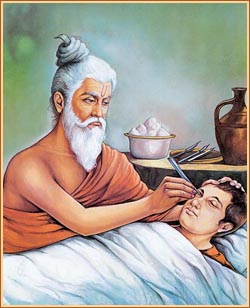

such as obstetrics, orthopaedics and ophthalmology. To consider an

example of the latter, he describes a method of removing cataract,

known today as ‘couching’. This was routinely practised

by Ayurvedic surgeons in India over the ages until the late half of

the twentieth century. For successful surgery Sushrut induced anaesthesia

using intoxicants such as wine and henbane (Cannabis indica). This

led A.O. Whipple in his Story of Wound Healing (1965), to comment,

must be accepted as a pioneer in some form of anaesthesia.”

The depth of his expositions in such a variety of faculties reflects

his brilliance and versatility. He asserted that unless the surgeon

possessed knowledge of the related branches, he does not attain proficiency

in his own field.

Like his guru Dhanvantari, Sushrut too, considered the knowledge of

anatomy obligatory for a surgeon to be skilled in his art. This necessitated

dissecting cadavers. Alongwith anatomy, Sushrut gives details of human

embryology in Sharirsthan, which are mind–boggling. This is

all the more astounding when we bear in mind that such detailed observation

is today only possible using microscopy, ultrasonography and X–rays.

To cite just one example, he mentions that the foetus develops seven

layers of skin, naming each layer and the specific diseases which

may affect that layer in adult life! (Sharirsthan IV–3). He

was also aware of diseases by genetic inheritance. He mentions many

congenital defects acquired from parents and those resulting from

indulgences of the mother during pregnancy. Therefore he advises her

to avoid exertion for the perfect development of the foetus. For instance,

she should avoid physical exertion, daytime sleep, keeping awake late

into the night, extreme fasting, fear, purgatives, travelling on a

vehicle, phlebotomy and delaying the calls of nature (Sharirsthan

III.11).

Sushrut’s era, as all down the ages, involved warfare. This

meant injury from weapons such as arrows often embedding as splinters

– shalya. He has categorised two types of symptoms for splinters

– general and specific – from which a diagnosis can be

made, of the type of splinter and its exact depth. He further details

the different symptoms for different splinters of bone, wood, metal

embedded in skin, muscle, bones, joints, ducts, pipes or tubes. He

then prescribes fifteen different procedures for removing loose splinters.

Two notable methods for problematic splinters though seemingly extreme,

are highly effective and innovative. If a splinter is lodged in a

bone and fails to budge, its shaft should be bent and tied with bowstrings.

The strings should be tied to the bit of the bridle of a tame horse.

While holding the patient down, the horse should be slapped or hit

with a stick so that it jerks its head. In doing so, the splinter

is forced out! If that fails, one could pull down a strong branch

of a tree and tie the splinter to it. One then lets go of the strained

branch, which will draw out the splinter!

Besides splinter injuries, Sushrut also deals with trauma. He describes

six varieties of accidental injuries encompassing almost all parts

of the body:

-

Chinna: Complete

severance of a part or whole of a limb

-

Bhinna: Deep

injury to some hollow region by a long piercing object

-

Viddha prana:

Puncturing a structure without a hollow

-

Kshata: Uneven

injuries with signs of both chinna and bhinna, i.e.

a laceration

-

Pichchita:

Crushed injury due to a fall or blow

-

Ghrsta: Superficial

abrasion of the skin

Besides trauma involving general surgery,

Sushrut gives an in–depth account and treatment of twelve varieties

of fractures and six types of dislocations, which would confound orthopaedic

surgeons today. He mentions principles of traction, manipulation, apposition

and stabilisation, as well as post–operative physiotherapy!

Being a genius and a perfectionist in all aspects of surgery he even

attached great importance to a seemingly insignificant factor such as

scars after healing. He implored surgeons to achieve perfect healing,

characterised by the absence of any elevation or induration, swelling

or mass, and the return of normal colouring. He went as far as prescribing

ointments to achieve this, managing to change healed wounds from black

to white and vice versa!

He also prescribed measures to induce growth of lost hair and to remove

unwanted hair. Such minute detailing reflects his deep insight, rendering

him the first surgeon in world history to practice a holistic approach

in treating surgical patients. According to Sankaran and Deshpande,

“No single surgeon in the history of science has to his credit

such masterly contributions in terms of basic classification, thoroughness

of the management of disease and perfect understanding of the ideals

to be achieved” (1976:69). To Sushrut health was not only a state

of physical well–being, but also mental, brought about and preserved

by the maintenance of balanced humours, good nutrition, proper elimination

of wastes and a pleasant, contented state of the body and mind.

Finally, from the patient to the surgeon. He gave a definition of an

ideal surgeon embodying all possible requisites, which has yet to be

improved upon even today. “He is a good surgeon,” he declares,

“who possesses courage and presence of mind, a hand free from

perspiration, tremorless grip of sharp and good instruments and who

carries his operations to success and the advantage of his patient who

has entrusted his life to the surgeon. The surgeon should respect this

absolute surrender and treat his patient as his own son.”

Sushrut’s excellence in surgery and original insights in all branches

of medicine render him the most versatile genius in the history of medical

science. His contributions have withstood the test of over three thousand

years. In the absence of sophisticated instruments available to us today,

his profound observations then may be attributed to two factors: grace

of a stalwart guru, Dhanvantari, and divine revelation through personal

sadhana – meditation. These observations of an ancient rishi,

today continue to intrigue researchers at the Wellcome Institute of

the History of Medicine in London and other similar institutions in

Europe, USA and India.

Reconstructive Surgery in India

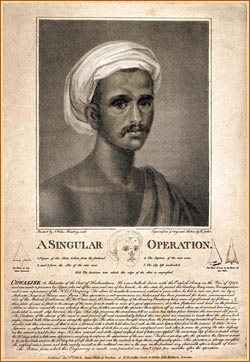

In 1792 Tippu Sultan’s soldiers captured a Maratha cart–driver

named Cowasjee (Kawasji) in the British army and cut of his nose and

an arm. A year later, a kumbhar (potter) vaidya in Puna reconstructed

Kawasji’s nose. Two British surgeons in the Bombay Presidency,

Thomas Cruso and James Findlay witnessed this skilful procedure and

noted the details. In October 1794, this account was published in

The Gentleman’s Magazine of London, describing it as an operation

‘not uncommon in India and has been practiced for time immemorial’!

This procedure, similar to that cited in the Sushrut Samhita, ultimately

changed the course of plastic surgery in Europe and the world. It

was different from Sushrut’s, in that Kawasji’s graft

was taken from his forehead. Sushrut grafted skin from the cheek.

To aid healing, he prescribed the use of three herbs and cotton wool

soaked with sesame seed oil in dressing the graft. After the graft

healed, he advocated cutting off the tissue joined to the cheek (Sutrasthan

16/18).

Regarding cosmetic surgery, Sushrut could also reconstruct ear lobes

and enumerates fifteen ways in which to repair them. Guido Majno in

The Healing Hand: Man and Wound in the Ancient World (1975), notes

that, “Through the habit of stretching their earlobes, the Indians

became masters in a branch of surgery that Europe ignored for another

two thousand years.” Sushrut meticulously details the pre–and

post–operative procedures. After stitching, for example, he

prescribes dressing the lobe by applying honey and ghee, then covering

with cotton and gauze and finally binding with a thread, neither too

tightly nor too loosely. Torn lips were also treated in a similar

manner (Sutrasthan 16/2–7, 18, 19).

Sadhu

Mukundcharandas

|

|